By Michelle Stirling ©2023

Image licensed from Adobe Stock.

Have I been “Beyak-ed?”

Someone has tried to cancel the publication of this paper which rebuts claims made by Sean Carleton of the University of Manitoba, about a paper that he did about Senator Lynn Beyak’s efforts to have people recognize the enormous good that Indian Residential Schools provided for thousands of children. Yes. Some children also suffered harms. Not everyone.

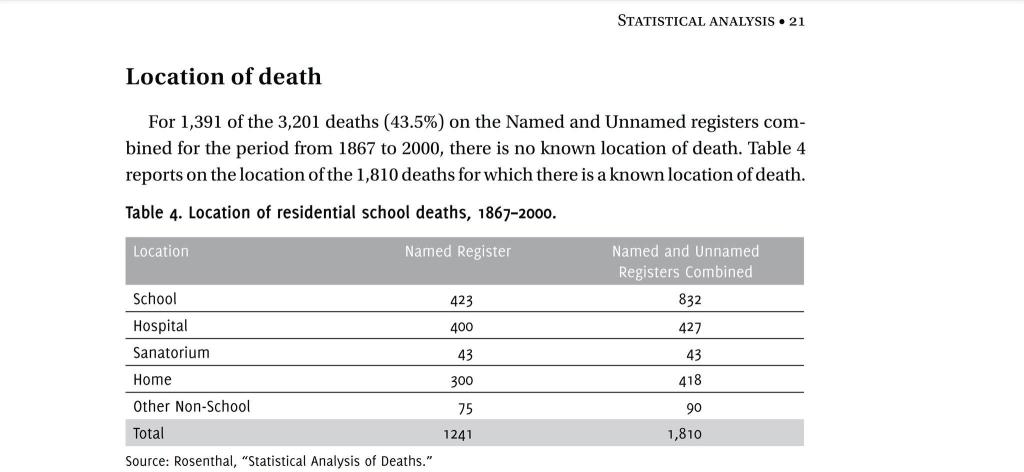

Carleton is a self-described ‘settler historian’ and part of the ever ballooning Indigenous and ‘pretendian’ grievance sector of Canadian society. There seems to be a parallel universe where mainstream Canadian life goes on as normal, while in settler historian-Indigenous grievance circles, there is an ever increasing ‘tab’ that mainstream society must pay for reconciliation. Most taxpayers are completely oblivious to these multi-billion dollar costs for questionable ends. At this point in time, based on the most recent budget, that tab is quite high. Of the approximately $35 billion deficit in the past fiscal year, about $26 billion (74.3%) was for the satisfaction of Indigenous claims. It should be recalled that Canada’s Indigenous population is about 1.8 million. Though people point to the reports of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) as evidence of mortal and moral wrongs, it should be remembered that only about 6,000 people (or 4% of the total residential school student base) provided their recollections to the TRC (not subject to evidence or cross-examination); more than 150,000 students went to Indian Residential Schools. Many were orphans, saved from the worst of fates by Indian Residential Schools run by Catholic Sisters and Brothers, or by other Christian denominations. Many who claimed they were forcibly taken to Indian Residential Schools were actually enrolled by their parents (if one looks at the records); and others were rescued from destitute, dysfunctional or dangerous homes.

As Robert Carney wrote, rejecting the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples report of 1996, “The work of the traditional boarding schools is similarly ignored in the chapter’s introductory section. The fact is that in addition to providing basic schooling and training related to local resource use, they served

Native communities in other ways. It would have been fair to acknowledge that many traditional boarding

schools, in some cases well into the twentieth century, took in sick, dying, abandoned, orphaned, physically and mentally handicapped children, from newborns to late adolescents, as well as adults who asked for refuge and other forms of assistance.”

Robert Carney, father of the much more famous Mark Carney (who curiously does not speak out in defence of his father’s life long research) , showed that government and media analysis of Indian Residential Schools were/are flawed from the get-go. Canada’s Indian Residential Schools saved thousands of orphans. Saved children!!

So, here is the abstract of my paper rebutting ‘settler historians’ and their world view. The full document follows. Enjoy!

~~~~

Settler Historians Need More Education, Less Ideology Rebutting Sean Carleton on Senator Beyak and Indian Residential Schools

Canada, once honored worldwide as a nation of peacemakers, is presently accused of genocide by China; condemned as a colonialist purveyor of genocide by a bevy of self-described ‘settler historians’ within Canada. The focus of the alleged ‘genocide’ is the establishment of Indian Residential Schools and the outcomes thereof for some 150,000 Indigenous students over the course of ~100 years. The evidence of this alleged heinous crime is said to be in recollections published in the reports of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2015, which, contrary to Carleton’s abstract, only claimed the schools constituted ‘cultural genocide’ – nothing more. Carleton (2021) assesses the instance of Canadian Senator Lynn Beyak attempting to provide diverse perspectives (typically positive) on Indian Residential Schools as a case of ‘residential school denialism.’ This work will provide historical evidence rebutting Carleton (2021) which presented theories of ‘denialism’ but little actual historical evidence to support his case.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly